In 2009 I began a novel, When I Fell,with the purpose of shedding baggage I’d been collecting: adapting to my son’s severe autism; resigning my academic job in order to try to give him the best start; accepting my own changing body (I was 40 and 42 when I had my children, physically further down the aging line than the other parents I was surrounded by, and by the time I began the novel, I was over fifty—and way into sagging!); witnessing my mother and step-father’s terrible decline in horrifying ways; and the retriggering of my own post-traumatic stress, which originally was caused by my father’s death while saving my family in a fire when I was nine. I was afraid of what I thought I would become: old and bitter.

I threw all that potential for plot in my creative pot, stirred, and created Evie Roberts, an 80-year-old woman who, facing a difficult surgery that will decide the quality of her the rest of her life, is forced by circumstances to finally face her three great disappointments: she could not marry the man she loved because he was “black” and she was “white”; she lost her first son to polio months before the Salk vaccine was available; and when she went to college in 1948, she was allowed to study only what then was called “a woman’s curriculum,” meant to educate women to run the homes owned by the men on whom they would depend. Evie was bitter, angry, as cynical as only a person who once had ideals can be. My goal was to somehow get her out of her situation and make her love life again in spite of its limitations, to connect with others when she had allowed herself to become isolated, judgmental, and afraid. In other words, I was trying to save myself.

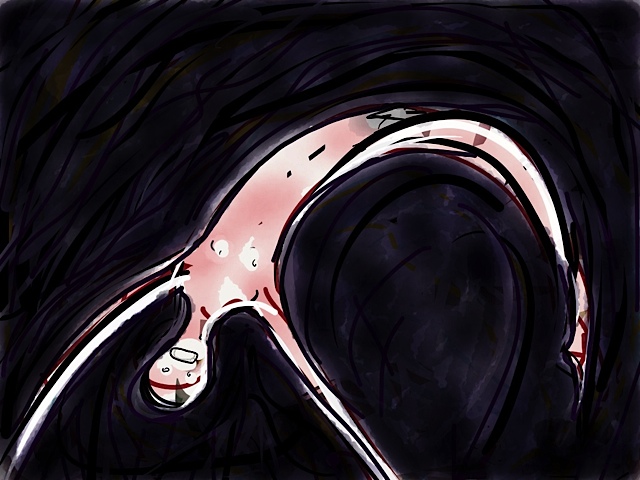

Right after I finished the book, a friend of mine, Kathy Skerritt, began posting drawings of hospital-related scenes, created on her iPad. Through abstract and representational images, Kathy documented her experience of being diagnosed and treated for breast cancer. In my mind, they powerfully resonated with the character I had created in Evie, who was stuck flat on her back in a hospital room, dependent on many people and circumstances beyond her control. I knew if anyone would understand Evie, Kathy would.

I asked Kathy to illustrate my book. She was attracted to the story of Evie’s redemption, and in the process of reading the novel drew 76 images for the book. That collaboration has been a highlight of my life—all conducted virtually and simultaneously within and along our own healing paths.

During this experience, two more people came on board. Musician, Michael Leasure, wrote music to accompany the plot and characters. Also, Musician and Materials Specialist, Stacy Kinchen, donated not only an original piano piece, but also some family photographs and images from his local historical society to provide us with real-life pictures of Evie’s times, which supplemented Kathy’s interpretive illustrations and provided historical context.

Working together provided us with a sense of community though we were never in the same room together. While my coffee was brewing at 5 am and I was about to begin writing, I would enjoy Michael’s music. If you listen as well, you will see how wonderfully he matches the overall feeling of the book and the lives of the characters with melody, and his thoughtful, intricate pieces cannot help but affect you.

Every time I got a batch of illustrations from Kathy, I crowed with glee! The range of emotions generated by her images was astounding. Like the text, her artwork blends sharp humor with great compassion. “The Death of Baby James,” “Evie’s Rising,” and the “Portrait of Mia” in particular are memorable. The three featured here are “Evie’s Fall,” “Animal Faces,” and “The Frogs.” There are 76 in total, all wonderful.

Stacy Kinchen has generations of family photographs and a keen interest in his hometown of Bellefontaine, Ohio, and so he provided us with many images that help support the background of the novel—though the novel does not happen in Bellefontaine. Instead of basing the story in a real place, I chose to invent a small, representative Ohio river town which once had been a transportation hub at the turn of the previous century. For me, as I was writing, the photographs were very grounding to the story and helped me create a sense of place.

I would encourage anyone with a vision to enjoy the freedom that creating an electronic book allows, such as colorful artwork without the exorbitant associated printing costs. We also supplemented the book with a website which includes the music and images, enhancing the original work here.

The following is the opening scene of the novel, When I Fell. I hope you enjoy it. We are planning on issuing a paperback version as well in the near future.

CHAPTER 1

Falling

The florescent lights above their heads seem too bright—and too far away—expanded into a white field way up high, where distant people speak slowly and soundlessly.

They cluster, staring down at me, pressing in on each other, stitched brows revealing there is little to do but wait for the doctor, their faces alarmed and, yes, looking like the faces of cows but deformed, as if viewed through the wrong end of a telescope.

Their noses fare the worse, and their lips—bovine, too—their ears poking out as they squat and try to call me back from where I’m going.

Confused, I vacantly stare with what have become tiny brown eyes struggling under drooping lids. This lack of response makes the Bovines feel inadequate. They stand up, look around, await instruction.

Not so the Equines.

What strikes me, having crashed there on the floor in front of the nurses’ station, is that while some people become Cows, others become Horses because, in the end, as you know, we grow to be what we are, the doctor suddenly standing over me, straddling me, syringe in hand.

Before my eyes he grows a long nose that widens as I watch from far below, its bridge lengthening above the narrow chin, becoming a muzzle with velvety lips and soft whiskers that cannot hide the square teeth yellowing, pushing forward as the jaw joints recede, and the hair balds to forelock.

Meanwhile, the people on the periphery of the hallway are developing into Frogs, lips thinning, wide mouths stretching, eyes bulging as they jump to orders from The Horse: “Don’t just stand there—get a gurney!”

For the Frogs, everything pulls back from the face, ears like drum skins almost disappearing, set behind cheeks that look like bone except when their mouths move, and I see that, even under these lights, through all this distance, the skin is still smooth, just amphibian, so many years in the sun on that rock finally catching up.

I have not looked in the mirror for ten years.

I have not looked in the mirror for ten years.

When they peer down at me and call ”Mrs. Roberts, are you okay?” I am still vain enough to wonder what they see.

Needle poised, the doctor appears dispassionate; he even grins.

Of course, during the day, on rounds with his nurse, he always mentions the weather as a suitable form of communication so that he may then dismiss me. Now, at eighty, for the first time in my life, I feel the prick and the sting.

Black Fox Literary Magazine is granted permission to reprint this excerpt from the original Web-e-Books® trade publication edition, copyrighted © 2015 – All Rights Reserved – to The Tri-Screen Connection, LLC, USA.

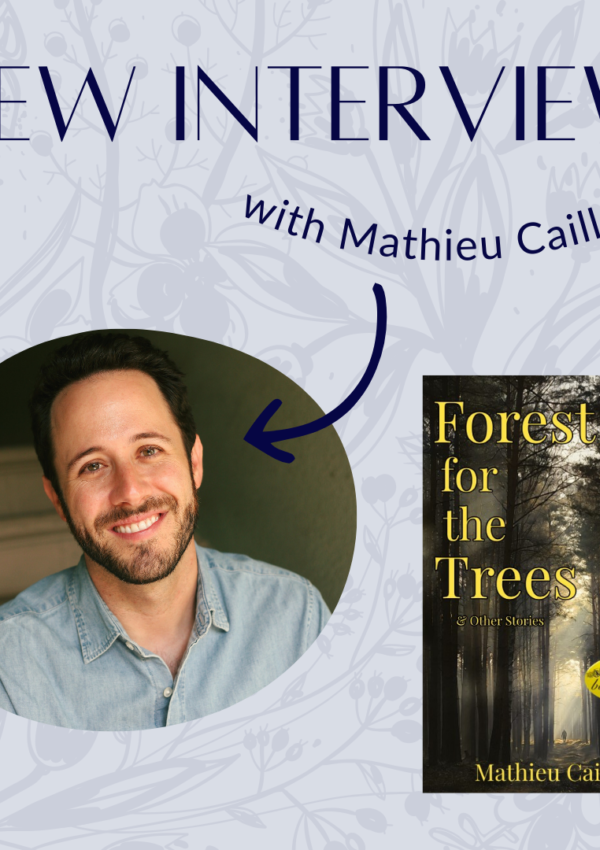

Over 300 of Sandra Kolankiewicz’s poems and stories have appeared in journals over the past 35 years. Turning Inside Out is available from Black Lawrence press. Finishing Line published The Way You Will Go in 2014. Web-e-Books released When I Fell in March 2015. Sandra lives in Marietta, Ohio, with her family.

Over 300 of Sandra Kolankiewicz’s poems and stories have appeared in journals over the past 35 years. Turning Inside Out is available from Black Lawrence press. Finishing Line published The Way You Will Go in 2014. Web-e-Books released When I Fell in March 2015. Sandra lives in Marietta, Ohio, with her family.