An interview by Alicia Cole.

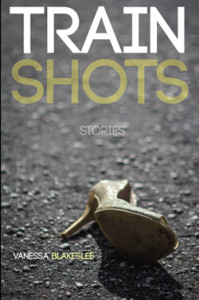

Vanessa Blakeslee is the author of the debut novel, Juventud (Curbside Splendor, 2015), hailed by Publisher’s Weekly as a “tale of self-discovery and intense first love.” Her story collection, Train Shots (Burrow Press) won the 2014 IPPY Gold Medal in Short Fiction. The book was also long-listed for the 2014 Frank O’Connor International Short Story Award and has been optioned for a feature film by writer/director Hannah Beth King. Vanessa’s writing has appeared in The Southern Review, Green Mountains Review, The Paris Review Daily, The Globe and Mail, and Kenyon Review Online, among many others. Finalist for the 2014 Sherwood Anderson Foundation Fiction Award, she has also been awarded grants and residencies from Yaddo, the Virginia Center for the Creative Arts, The Banff Centre, Ledig House, the Ragdale Foundation, and in 2013 received the Individual Artist Fellowship in Literature from the Florida Division of Cultural Affairs.

Vanessa Blakeslee is the author of the debut novel, Juventud (Curbside Splendor, 2015), hailed by Publisher’s Weekly as a “tale of self-discovery and intense first love.” Her story collection, Train Shots (Burrow Press) won the 2014 IPPY Gold Medal in Short Fiction. The book was also long-listed for the 2014 Frank O’Connor International Short Story Award and has been optioned for a feature film by writer/director Hannah Beth King. Vanessa’s writing has appeared in The Southern Review, Green Mountains Review, The Paris Review Daily, The Globe and Mail, and Kenyon Review Online, among many others. Finalist for the 2014 Sherwood Anderson Foundation Fiction Award, she has also been awarded grants and residencies from Yaddo, the Virginia Center for the Creative Arts, The Banff Centre, Ledig House, the Ragdale Foundation, and in 2013 received the Individual Artist Fellowship in Literature from the Florida Division of Cultural Affairs.

Black Fox Literary Magazine: Your work is peopled with alienated female protagonists within alien environments–where did this focus come from?

Vanessa Blakeslee: I hadn’t so much thought about my female protagonists as alienated, but I suppose they are. I’ve lived a fairly alienated life myself; as the autistic female raised in a working class household rife with dysfunction and conflict. From the earliest, I can remember I’ve lived in my own world. I’m wholly incapable of dealing much with the real “daily grind,” unfortunately. The downside of this extreme introversion is that it makes finding fulfilling intimacy difficult. I suppose most of my writing up until this point has flowed from that emotional impetus of painful loneliness and escape. Only now I have a wonderful partner in my life, so I am somewhat unmoored and apprehensive about where my fiction will come from next.

That said, alienation and “fish out of water” stories have always made for great literature, and I’ve been drawn to fiction set on foreign soil ever since reading Heidi. Juventud very much is inspired by Hemingway, Forster, Graham Greene, Isak Dinesen, etc., as well as a few specific contemporary works. Caucasia by Danzy Senna helped me hone the voice of Mercedes in later drafts. Senna’s is very much a novel about identity and estranged parents, and how the narrator perceives her reality as a child vs. how she later comes to view those events as a young adult. Cat’s Eye by Margaret Atwood, also about memory although structurally different and rendered in present tense. I often turn to Atwood for her astounding imagery, and smart, fresh, funny turns-of-phrase. The Lover was an influence, for the lyrical way Duras depicts a fifteen-year-old’s discovery of forbidden sex in the tropics. And there are others, too many to recall.

BFLM: How did Train Shots develop as a collection?

VB: Many of the stories in Train Shots I began as an MFA student at Vermont College. In the years since, I kept revising them as they were accepted for publication in literary journals and along the way, kept sending out the manuscript to small press contests for book-length collections. Twice the full manuscript placed as a finalist, although under different titles—I kept playing with the stories to include, the order and the title. Just as I found myself exhausted of submitting it through the contest system, Ryan Rivas, the editor at Burrow Press, approached me about possibly launching my debut collection. At the time I was writing a craft blog for the Burrow Press Review, and he had come to know me as a hard worker and an active member of the literary scene, and he knew I’d been publishing in well-regarded places. He read the manuscript in January, 2013, and afterwards contacted me with a firm offer. For the next several months, we went back and forth deciding which stories to swap out and which to include.

VB: Many of the stories in Train Shots I began as an MFA student at Vermont College. In the years since, I kept revising them as they were accepted for publication in literary journals and along the way, kept sending out the manuscript to small press contests for book-length collections. Twice the full manuscript placed as a finalist, although under different titles—I kept playing with the stories to include, the order and the title. Just as I found myself exhausted of submitting it through the contest system, Ryan Rivas, the editor at Burrow Press, approached me about possibly launching my debut collection. At the time I was writing a craft blog for the Burrow Press Review, and he had come to know me as a hard worker and an active member of the literary scene, and he knew I’d been publishing in well-regarded places. He read the manuscript in January, 2013, and afterwards contacted me with a firm offer. For the next several months, we went back and forth deciding which stories to swap out and which to include.

Ryan’s philosophy is that assembling a story collection is a lot like putting together a music album, and he’s absolutely right–we left out certain stories not because they lacked merit, but because the ones chosen must speak to each other in a particular, resonating way. I’d describe the process as very hands-on. I absolutely loved the thorough scrutiny we both brought to the manuscript as a team. On my own, I’d never been able to come up with a satisfying order, and Ryan had a terrific eye—and ear, I might add—for which stories belonged where, a vision of the book as a living, breathing whole. Whereas I’d worked on the stories for so long on my own, I think I’d become too close to them. So I’d say I was ultimately surprised and thrilled by the finalized “playlist,” not to mention profoundly grateful.

I was also surprised by how heavily we edited, and even revised in some cases, certain stories. All of them had been published before, and it’s easy for emerging writers, I think, to assume that once a journal has published a story, there’s no more work to be done. Far from the case. This is the stage where you have the opportunity to refine and bring your work to the next level, so you’re really presenting your best—to zero-in on repeated diction and unwieldy syntax, to make sure the final notes of each story truly sing. We had a deadline, of course, but we took our time. I believe our efforts paid off.

I had always wanted to include the flash fiction, “Clock-In,” as the opening, as it uses second person and literally invites the reader into the world of the book. “Train Shots” is one of my most memorable and unusual stories, so we knew we’d include that one from the beginning. The tone and theme made it a ready contender for final spot, and usually the placement of the title story bears weight, so that made sense—Train Shots. But also there’s a double-meaning to the phrase “train shots.” In one sense, the collection is a journey, the reader peering in on different characters in various settings, glimpsing a “shot” of these individuals’ lives before the train zooms on. Then in the title story itself, P.T. eats dinner at a dive-bar alongside the tracks in Winter Park, where the bartenders offer “train shot” drink specials when the trains go by.

As for the order, we probably considered twice as many stories than what ended up making the final cut. We eliminated ones that would contain beats or subject matter too similar to others, and sought a balance in narrative perspectives and moods, from light to dark. I recommend to anyone who is seriously putting together a collection to get together with a trusted writer friend or teacher and employ another pair of eyes, at least, to help you select and juggle the order—doing so would have saved me a lot of grief and time.

BFLM: What’s your creation process? What do you need? What do you avoid?

VB: Well, speaking from where I am now, I know if I’m working on a novel from the beginning based on the vision in my head—how much I can see of the characters, significant moments occurring against a backdrop of time and place. I spend a tremendous amount in the pre-writing stage, asking broad “what if” questions of the premise, then more specific questions about the characters and plot as more of the storyline takes shape. I’ll write a chunk in my notebook, then go back to my notes and draw little diagrams, time lines and such—sometimes I’ll even work from calendars to keep the time frame straight, in a denser Munro-like story that takes place over several weeks or months. As much as possible I like to figure out a piece’s restrictions before I sit down to draft, whether those restrictions are structural or springing from historical backdrop, location, season, etc. This greatly helps eliminate certain possibilities for where the story can go. I’ve heard some writers speak of this as figuring out the story’s “container” and that’s very apt. For this new novel I’m going to create a firmer outline than the looser array of sticky tabs and notecards I worked from during Juventud. I’ve come to believe a clearer outline is absolutely necessary before you begin, otherwise you’ll find yourself a hundred pages in, and going down a lot of blind alleys. I’m determined to work smarter this time, and a novel is all about structure. Inevitably you’ll make changes and discoveries as you write, so there’s no need to fear The Outline. You’re just making a map.

VB: Well, speaking from where I am now, I know if I’m working on a novel from the beginning based on the vision in my head—how much I can see of the characters, significant moments occurring against a backdrop of time and place. I spend a tremendous amount in the pre-writing stage, asking broad “what if” questions of the premise, then more specific questions about the characters and plot as more of the storyline takes shape. I’ll write a chunk in my notebook, then go back to my notes and draw little diagrams, time lines and such—sometimes I’ll even work from calendars to keep the time frame straight, in a denser Munro-like story that takes place over several weeks or months. As much as possible I like to figure out a piece’s restrictions before I sit down to draft, whether those restrictions are structural or springing from historical backdrop, location, season, etc. This greatly helps eliminate certain possibilities for where the story can go. I’ve heard some writers speak of this as figuring out the story’s “container” and that’s very apt. For this new novel I’m going to create a firmer outline than the looser array of sticky tabs and notecards I worked from during Juventud. I’ve come to believe a clearer outline is absolutely necessary before you begin, otherwise you’ll find yourself a hundred pages in, and going down a lot of blind alleys. I’m determined to work smarter this time, and a novel is all about structure. Inevitably you’ll make changes and discoveries as you write, so there’s no need to fear The Outline. You’re just making a map.

All of this can take anywhere from a couple of days preparation for a new short story, to weeks or longer for a novel. For me, novels brew in my subconscious for years before being born.

Then once I sit down to write, I draft fairly quickly. Lately, my first drafts are of a much higher quality than they were, say, for much of my twenties. But they still need copious revision.

Writing for me is an ingrained habit, not a discipline. I’ve always preferred to settle into my day, and usually spend my first hours with a cup of tea, answering emails, reading articles, and running errands. By midday I’ve grown fed up by those things, and that drives me to my desk or notebook, where I’ll work uninterrupted for hours. I realize this is quite opposite from what so many writers I know practice—getting up and writing first thing, morning as a sacred time of day, etc. I’m more likely to look up and discover that it’s 12 a.m., and I had better get off the laptop as my eyes are watering.

BFLM: How have your residencies shaped your writing?

VB: Residencies have been invaluable to my creative well-being, in that they provide the ideal combination of restoration and stimulation. Anxiety is the enemy of creativity, and I’ve had an anxious temperament ever since I was a child. Add to that the increased anxiety of our constantly plugged-in, 21st century pace and finding your way to the tranquil headspace where your best ideas arise is near impossible. This headspace is especially crucial in the inception and first-draft stages of a work. For instance, I’ve just returned from a month in Wyoming at Brush Creek Foundation for the Arts after a very hectic year of travel and presentations for my debut novel, Juventud. I spent a lot of time just soaking in the alien scenery (the high desert is about the most startlingly different landscape than Florida, a distance which may have helped me “see” my hometown subject better). I hiked a lot and cleared my mind. I read, researched, and took dozens of pages of notes for my next novel. I doubt very much I would have progressed that far at home. Residencies are often in rural and stunning settings–you can’t underestimate the nourishment that beauty and tranquility bring to the creative process. Not to mention, many residencies feed you! Freeing up further mental space from grocery lists.

BFLM: What has been most important to your development as a female writer? What has been most detrimental? How do you steer for the good and avoid the pitfalls?

VB: As a female writer, I would say not getting pigeon-holed by those very terms—I see myself as a writer of stories, and by that I mean human stories, not stories by a certain set of people. I very much have an androgynous mind and sense of self, and I think I write from that place. I’m equally vested and curious about telling stories from people of different genders and demographics, just as long as I tell them convincingly.

At this stage of my career, I think not comparing myself to where I see other emerging authors is crucial. A few years into pursuing a literary career seriously, and you become aware pretty quickly of the competition and the inherent unfairness—the bestowing of big awards and recognition is a very political game in the arts, and you see the same small group of anointed writers rewarded time and again. Not that those writers aren’t talented, but the fact is there are many, many others who are equally if not more talented and yet you’ll never hear of; they couldn’t pay to attend the opportunities to make the key connections, and so their names just don’t make it in the spotlight. That unfairness can be very dispiriting if you let it. That post-book publication reality forces you to a crossroads where you have to dig deep and ask yourself, so why I am really doing this? How much of it is about external validation of my work? Do I have the strength to continue to write on in obscurity? Lately, I’ve been thinking obscurity can be a wonderful thing. I don’t know if I could handle starting another novel-length project again had my previous book been a huge commercial hit. Success and big prizes can be truly paralyzing, even more so early on. Look at Harper Lee.

Always, the question remains: what matters to you? Is this story absolute essentially for the world to hear? “You’ll never write alone again,” Paul Harding said to me when he visited Orlando, and I told him my first novel was about to be published. He’s right. You have to either find your own way back, or quit.

I will add that finding a certain amount of work-life balance and financial security has also been important. For me, that means I keep my overhead as low as possible and work a couple of part-time, low-stress jobs in order to pay my bills (I work at a bookstore and also teach on-line part-time). The “gig economy” lifestyle is stressful but allows for a certain amount of freedom I need to feed my imagination, stay in physical shape (which I’ve come to believe is essential for me to undertake the marathon of novel-writing, if I hope to do it well), and not use up mental energy elsewhere. I’m extremely frugal and this allows me to spend judiciously—to go to residencies and conferences, for example, which nurture my work.

BFLM: What other authors are you reading and why?

VB: I’ve just finished reading the novel-in-stories, Forty Martyrs, by fellow Burrow Press author Philip F. Deaver—a superb masterwork in realism laced with humor, in the tradition of Sherwood Anderson and Elizabeth Stroutt. In fiction I’m also working my way through Jeff Vandermeer’s Area X series. But mostly I’m immersed in nonfiction titles and taking notes for the new novel, set in a near-future Orlando and Space Coast. I’ve just finished Melbourne Village: The First Twenty-Five Years 1946-1971 by Richard C. Crepeau, which is about the failed utopian community founded by famed “back-to-the-land” guru Ralph Borsodi, that became the present-day town of Melbourne Village. Borsodi was a charismatic, controversial figure who has become an icon in the “off the grid” community. Reading the case study of why such intentional communities founded on lofty ideals almost always fail in the USA has been revealing, and not altogether surprising. I’ve also just started The Modern Survival Manual: Surviving the Economic Collapse by Fernando “Ferfal” Aguirre, which is a fascinating read—part memoir, part instructional manual, and self-published actually. While perusing various “prepper” blogs and familiarizing myself with the whole survivalist subculture in this country, I stumbled across his, which stands out for the simple reason that it is based on factual firsthand accounts—Aguirre and his family survived the 2001 economic collapse of Argentina. His has been an invaluable resource of how human beings actually behave in a crisis, versus the many Hollywood-influenced fantastical scenarios of most other survivalist manuals and blogs flooding the marketplace, and their far-fetched imaginings of various “collapse” situations. Aguirre’s English isn’t perfect but his substance makes up for the flaws. He has a newer title called Bugging Out and Relocating: When Staying is Not an Option, which I’m looking forward to diving into next. So I’m not even in the drafting phase for the new novel yet, but the project is already a tremendous amount of fun to research. You could say I’m obsessed.

BFLM: What other artists/mediums inspire you?

VB: I’m constantly inspired by artists in other fields—the visual artists, composers, filmmakers, and the like that I meet at colonies and residencies, and among creative circles in Orlando. When I was immersed in Middle Eastern dance, I found my fellow dancers in the company and instructors incredibly inspiring, and still do. Certain directors, screenwriters, and character actors inspire me—the late Philip Seymour Hoffman, Kate Winslet, Joaquin Phoenix, Daniel Day-Lewis, for example—the actors who really know how to inhabit a character. In music, I love groups like Sigur Ros and Lady Gaga—artists who conjure up a whole imaginary, sometimes mythical landscape, beyond the lyrics and notes. That’s vision, when the work exhibits a certain emotional depth and scope. One that’s mysterious, bigger than the mere instrument of the artist and fueled by the subconscious.

BFLM: What’s next in your writing career?

VB: This past year I’ve been revising stories for the second collection that I just submitted to my editor. In between I’ve been working on essays and book reviews. Lately, I’ve been drawn to speculative and dystopian fiction as I mentioned earlier, and laying the groundwork for this darkly comic futuristic novel set in central Florida. I haven’t started writing it just yet. The project requires more research and a day trip or two. But I’m excited to start.