An interview by Alicia Cole.

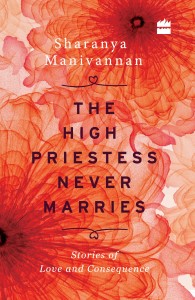

The poet Sharanya Manivannan’s first book of fiction, The High Priestess Never Marries, has been described in The Establishment as “a tour de force of language, desire, and ancestral heartbeats.” It has just been published by HarperCollins India, and is available from Amazon in hardback and Kindle formats.

The poet Sharanya Manivannan’s first book of fiction, The High Priestess Never Marries, has been described in The Establishment as “a tour de force of language, desire, and ancestral heartbeats.” It has just been published by HarperCollins India, and is available from Amazon in hardback and Kindle formats.

Black Fox Literary Magazine: You’ve chosen the High Priestess from the tarot deck for the title of your new collection. This is a trump: a less mutable card. What is unchangeable in yourself? What themes in your work?

Sharanya Manivannan: It’s not easy to hold a mirror up to oneself and say: these are the things I know are true. For now, I will say that I hope I never lose the ability to remain soft, to ask difficult questions gently, to stand my ground, to weep when necessary, and to laugh often and freely. As for my writing, the bedrock is really composed of: ancestral silencing, love and its loss, the natural world, and divine grace. It couldn’t exist otherwise.

BFLM: Are you actively seeking The Hierophant, the High Priestess’ counterpart? Your writing speaks of such longing that I have to ask, as “teenage magazine column” as this question may sound. Are you eager or afraid to be confronted with your book’s title outside of its pages? What does this say about your relationship with your writing?

SM: I once had a tarot reading in which the reader herself, who was friendly and curious, asked the question “when will [I] get married?” because she wanted to know. I was at a point when I had a strong intuition that a romantic nemesis of mine was about to irreparably injure our story (which he did), and marriage was really the last thing on my mind. She drew the High Priestess card. As she started to tell me about how the card meant that once I truly believed in finding love, etc., etc., I couldn’t help but laugh. I had to stop her to say, “You know that book I’m writing? It’s called The High Priestess Never Marries.”

SM: I once had a tarot reading in which the reader herself, who was friendly and curious, asked the question “when will [I] get married?” because she wanted to know. I was at a point when I had a strong intuition that a romantic nemesis of mine was about to irreparably injure our story (which he did), and marriage was really the last thing on my mind. She drew the High Priestess card. As she started to tell me about how the card meant that once I truly believed in finding love, etc., etc., I couldn’t help but laugh. I had to stop her to say, “You know that book I’m writing? It’s called The High Priestess Never Marries.”

In my personal understanding, I don’t think of the Hierophant as anything other than a professional comrade of the High Priestess. Because I love her autonomous. That doesn’t preclude romance, lust, intensity, forging familial bonds, and friendships. That doesn’t preclude partnership, of any kind. That doesn’t preclude solidarity. That doesn’t preclude love. This is where I’m at in my own life, as well.

BFLM: You have a strong dichotomy in your work: love and spirituality/esotericism. How do these two interplay in your collection?

SM: But it isn’t a dichotomy at all. The idea of sensuality and spirituality being binaries is at the core of why major religions engineer such trouble in the world today. Because pleasure has no place, there is self-loathing turned into fearmongering about the other. There is violence and violent rejection. There is gender discrimination. There is the fundamental idea that women’s bodies are polluted and that counting them as property is the only way to control this pollution. There is hatred toward queer peoples. There is hatred toward diversity and multiculturalism. Let me say this as a believer: that’s a whole lot of bullshit. For me, there’s no compartmentalization between my faith, my politics, or my personal life. That’s why there’s so much of both (spirituality and sensuality) in my writing. Because they’re inseparable. If we put them back together, if we don’t see them as distinct and contradictory, much will heal in the world.

BFLM: There is such a ripeness to your stories of love and loss. How do you know when a story, like a mango, is ready for picking and consumption?

SM: All stories have their own time. “The Huluppu-Tree,” for instance, woke me up in the middle of the night. I bolted upright in bed, wrote 800 words and went back to sleep. I wrote “Nine Postcards from the Pondicherry Border” in an actual epistolary fashion, because as soon as I finished one section I mailed it off to a friend, and in this way the whole story arrived, just as postcards do. “Conchology” and “Sweetness, Wildness, Greed” took years and years: I’d taken the journeys, I’d stayed true to the early glimpses I’d had, but it still took so long for all the words to appear on the page. A story will come out differently based on who you are at the time of writing. I simply trust that it isn’t that I am waiting for the story, but that it is waiting for me – to arrive at the place where I am most receptive to it, when its frequency and mine resonate. Writers’ blocks (I’ve been in one for over a year) are difficult emotionally. But I believe in this, and it is a source of great reassurance.

BFLM: In the title story, there’s a statement: All Indian men are secretly terrified of women. It’s the state of the nation. What is it like living in a matriarchal patriarchy? How has this shaped you as a feminist writer?

SM: I’m not sure I understand what a “matriarchal patriarchy” means, because I think India is a place where women are very much patriarchal agents. I know of matriarchs within this system, but they are glitches in the system, and their spheres of influence are frustratingly limited. These hegemonies are perpetuated not just by active participation but by tacit complicity. A really simple urban example would be the woman who, after a few years of failed relationships, “chooses” an arranged marriage. Perhaps in her own life there’s little to regret, but all she really does is to enter the establishment because it will protect her (as long as she complies). She knows what the establishment does to women and disenfranchised people at large, but their lives are less relevant to her than her own comfort. So she chooses to allow caste to flourish, to defer to a domestic hierarchy, even to ignore her own heart. In doing so, she not only reinforces the structure, but withdraws abstract solidarity from those who reject it or try to flee it.

The woman who says that line in the story, the eponymous High Priestess in fact, is indeed someone men are terrified of, because of how she plays with and wields her own power. But the woman she uses it to describe – a conservative, hostile older woman – is terrifying only because of the power vested in her by the force of the establishment, the exalted Indian patriarchy.

BFLM: What is your feminism? How do you hope your feminism shapes your surroundings, literary and otherwise?

SM: Lived practice. Not a performance. Evolution based on listening, learning, questioning. Absolutely intersected not only with other social justice movements but to concepts like compassion and rigor. Very difficult, but also very natural.

I spoke earlier about the limited spheres of influence even a matriarch who challenges the system has, and at this stage I am maverick, not matriarch. And I’m aware I will only reach so many people. My instrument after all is writing, which has no respect in the country I live in (and writers are in fact now regarded outright as political malcontents). But I will try. In the past, I have heard from readers who told me my poetry helped them during a divorce or a bereavement. I really hope The High Priestess Never Marries will help people with breakups and unrequited affection, and help them see both loneliness and partnership from alternate perspectives. Love is a feminist issue.

BFLM: What works of art (including writing) must you have near you? What most inspires you?

SM: I’m surrounded by books and colors, decorative trinkets, jewelry, paintings, and fabrics. I like to have trees and flowers within my view (in summers, the flowering trees in my city include the rusty shield-bearer, the laburnum, the gulmohar, and at surprising corners, the jacaranda). I also enjoy scents, and I often keep a fragrance or a lotion nearby as I work. And music. I listen to all kinds of music, and usually play some while I work. But when I’m actually writing, I can’t hear anything. I will surface from a deep dive into words and find that six tracks have gone by in a carefully curated playlist and I hadn’t heard a single chord.

BFLM: What are you working on now?

SM: A novel I’ve been trying to write since I was 19, a graphic novel that I’m illustrating as well, a novella that I intuit I will write in a deluge (but to all of these a plaintive plea – when, when will I be ready for the words that are waiting?). And manuscripts of poems and stories that I build slowly, like a variegated set of enamel piggy banks into which I slip coins from time to time.

Sharanya’s poetry appears in Black Fox Issue 12.