An interview by Alicia Cole.

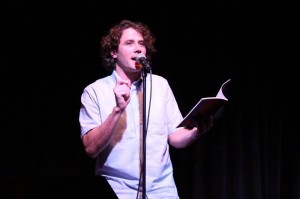

A singer-songwriter and poet from Atascadero, California, Ephraim Scott Sommers is the author of The Night We Set the Dead Kid on Fire (Tebot Bach 2017), winner of the 2016 Patricia Bibby First Book Award. Having received his PhD from Western Michigan University, he is currently Assistant Professor of Creative Writing at Winthrop University in Rock Hill, South Carolina where he lives with his fiancé. Recent poems, essays, and stories have appeared or are forthcoming in Beloit Poetry Journal, Cream City Review, Minnesota Review, Prairie Schooner, Tri Quarterly, Verse Daily, and elsewhere. For music and poems, please visit: http://www.ephraimscottsommers.com/.

A singer-songwriter and poet from Atascadero, California, Ephraim Scott Sommers is the author of The Night We Set the Dead Kid on Fire (Tebot Bach 2017), winner of the 2016 Patricia Bibby First Book Award. Having received his PhD from Western Michigan University, he is currently Assistant Professor of Creative Writing at Winthrop University in Rock Hill, South Carolina where he lives with his fiancé. Recent poems, essays, and stories have appeared or are forthcoming in Beloit Poetry Journal, Cream City Review, Minnesota Review, Prairie Schooner, Tri Quarterly, Verse Daily, and elsewhere. For music and poems, please visit: http://www.ephraimscottsommers.com/.

Black Fox Literary Magazine: Your work often speaks of violence in tragic bursts, and speaks of tragedy in general. What is your process of turning violence and tragedy into creation?

Ephraim Scott Sommers: First off, Alicia, thanks so much for allowing me the space to answer some questions about my new book, The Night We Set the Dead Kid on Fire. All you good people at Black Fox have been so awesome to me!!

To answer your question, I want to write about moments I don’t have completely figured out, so the ‘not knowing’ how I feel about a particularly violent or tragic moment from my past becomes the impetus for me to write the poem or the song at all, to dig around inside that particular moment to answer a demanding question I might have about it. For me, too, the poem is the place to begin a conversation with myself about a particularly difficult set of feelings that I might not yet have found the words for.

Also, I’m not sure if it’s this way for you, but my emotions about an experience seem so often intertwined in a kind of soupy mess with my thoughts about that experience, with how I think I ‘should’ feel about it, with how other people might feel, with my imagination, with the sensory images of that experience, and with what the sonic quality of that experience might be. All of these things (feelings/thoughts/craft concerns) are fighting to be heard during the writing process of the poem. I’m a writer and a musician of improvisation. I’m trying to listen and feel and sense my way through it. I’m searching for a new discovery. I have some tools I’ve been honing in my reading and writing, some metaphors, some sounds, some sentences and some possible sources of tension, and armed with these tools, I drop down inside a moment not knowing where the tunnel might lead, and I try to dig down through the darkness and earth to the center of that difficult moment, to touch it with my hand, and, then, hopefully, with a little luck, I find the right way up out of the hole with a moment to show you, and the poem is born.

BFLM: The bizarre everydayness is evident in your work. How long have you been fascinated with such things? How long have they influenced your writing?

ESS: If you look at all the major movements of art, literature, and music, many of those are a direct rejection of the movement that came before it. We call an artist a visionary when they reinvent their art in a new way, when they do something no one else before them has done. Jimi Hendrix plays a right-handed guitar both left handed and upside down, and he lights that guitar on fire. The world is never the same. We get sick of routines. We want something new, something different, something that sprints away in the opposite direction of the main stream.

I’m more interested in the strange and the bizarre because, every day, in a million different ways, we do things the exact same way as everyone else. Sometimes, as in politics or issues of social justice, we need to focus on the ways that we are the same. In art, I want to celebrate the differences and rebel against sameness. I want to celebrate the weird shit we do when no one is looking. I think all of us love to look at strange things because we don’t have them completely figured out. They catch our eye.

BFLM: Speak of your award-winning first book: The Night We Set the Dead Kid on Fire. How was it developed?

ESS: I believe every writer has to discover for themselves what it is they care about most in the world and then find a way to create something about it. But for a really long time, even in Grad School, I didn’t think that I could write poems about my hometown and the people I grew up with because I hadn’t read anyone in my literature classes that wrote about those kinds of characters: blue collar people, truckers, mechanics, alcoholics, dishwashers, drug addicts etc. So, I was writing all sorts of shitty poems about throwing imaginary apples at police cars, just wacky word play without any grit, without any personal stakes.

Then I read Phil Levine, a blue-collar poet from Detroit who showed me that there is a place for these kinds of people and these kinds of experiences in the conversation of poetry. Once I felt like I was given that permission, I had decades of memories from my own lived experience to comb through and write about. I remembered what I saw growing up, and I tried to sing it back to life, all the fist fights and the STIs, and the blood and the mud and the funerals and the laughter, the good and the bad. I wrote most of the poems from this book during a three-year period.

I love my hometown of Atascadero, California and the hard-working people who live there, and I dedicated the book to them. I wanted to sing about the experience of living there in a way that made holy what everyone else had always thought of as ugly.

Shameless plug: if you’d like to buy a signed copy of my book, please go here: www.ephraimscottsommers.com/contact

BFLM: Your music echoes your poetry in certain ways while retaining a gorgeous sense of romance. When did you start making music and how have you grown in this field?

ESS: Thanks for the kind words about the songs. I’ve been a musician since 2001 when I joined and sang for a funk rock band called Siko (pronounced See-Ko) (www.myspace.com/siko). We put out two full length albums and an EP in the ten years or so we were together and toured nationally. Since that time, I’ve put out a solo record called Stones & Smoke which you can listen to and/or buy on my website. As a solo artist, in 2010, I got a chance to tour in England and played some really small shows in Costa Rica.

Recently, I’ve lived in three states in the last two years for work, so I haven’t had time as much to play live, but my fiancé and I have settled in Rock Hill, SC, and I am currently looking for some musicians to get a new project going. Poetry is a lonesome go, so I find great joy in being able to collaborate with others in the creative process. There is no feeling in the world like being in a band, making sound with other people, and then watching the sounds you created together literally moving the people in the room to dancing.

BFLM: How does your job as Assistant Professor of Creative Writing augment your work?

ESS: A long time ago, I realized that if I could find a job that would directly feed into my art and put me around other artists, then I’d probably enjoy that job much more than anything else and be a much happier human being. This is why I’ve tried for so long through schooling to get where I’m at now. I am exceptionally grateful to be able to teach creative writing for a living. I consider myself so lucky in that I get to talk about making art with bright young minds at Winthrop University who are continuing to challenge the boundaries of creation in so many new and exciting ways. I get to read work by writers from vastly different socio-economic, cultural, and ethnic backgrounds, and not only does this make me a better human being, it helps inspire me to be a better artist. I can’t think of another job that seems so well suited to my interests.

BFLM: What are your favorites of your own poems?

ESS: Normally, my favorite poem is the last one I’ve written or a poem I don’t get sick of. One of my favorite poems from The Night We Set the Dead Kid on Fire is below, and it first appeared in the pages of Black Fox last year. I like this poem most because I feel that I achieved what I set out do in most poems, to sing you a difficult story. I really tried hard to let the music and the narrative complement one another in this poem.

THE HARDEST THING (from The Night We Set the Dead Kid on Fire)

No coming together without letting go,

Eva reminds me and reminds me,

for love, she believes, is two people trying

for the same place, and her I will follow,

therefore, into the future neighborhoods

of future cities until my elbows are

jimmied further open, for if forgiveness is

a backyard, she has taken down the fences,

filled the pool, and invited everyone

to the piñata. We are always gathered here

together as balloons so we may rise, she hums

and hums, and here her forgiveness comes

despite her jawline, her hair flowered

and floating the lawn chairs toward the stereo’s

gentle question. Who takes my daughter?

Her father asks, and though she takes me,

though I’ve always said we were born

to get even, she revises my mouth to say

now we were born for getting over. She vows,

today, we will U-Haul up our memories

and send them away, and I am almost ready

to unlock like she has, to unlatch my fingers,

to uncock them and let in her father’s

hand, and though metal against a woman’s

mouth is an almost impossible thing for a man

to un-remember, and though across

the courtyard, my Aunt Diane scorches

a pork shoulder with a blow torch

and spits Skoal onto the back of a golden

retriever, still I am almost ready

to receive the same father’s hand

that sixteen years ago drove a crowbar

through my girlfriend’s chin.

BFLM: What are your favorites of others’ poems?

Here are three poems by other authors I’ve really dug recently!

“Winter” by Chen Chen https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poetrymagazine/poems/142861/winter

What I love about Chen’s poem is that we don’t realize we’re in a love poem until the very end. It sneaks up on us because the speaker is so playful throughout, and they don’t get serious until the absolute last narrative moment of the poem. I cannot get enough of that surprise tonal shift, and I love the mixture of the beautiful and poopy! We need more poop in poems! Poem challenge!

“Fat Fuck” by Diamond Forde

https://theoffingmag.com/poetry/fat-fuck/

“That’s the kind of sick bitch I am.” Damn, what a monumentally powerful and direct voice that owns itself and pits itself against the world. This poem is ferocious in all the right ways! This poem has teeth!

“Party in the U.S.A” by Franklin KR Cline

http://banangostreet.com/issue8/franklin-k-r-cline/

What I dig most about Franklin’s poems, and this one in particular, is that he often subtly asks the reader, “Why can’t we put everything in our poems?” His is a truly democratic poetry, and this is an oceanic long poem a la Whitman and O’Hara. Go get his new book, So What, over at Vegetarian Alcoholic Press: http://www.vegetarianalcoholicpress.com/titles/so-what.

BFLM: If you could keep only three books with you, what would they be and why?

ESS:

Invisible Cities by Italo Calvino

100 Years of Solitude by Gabriel Garcia Marquez

The Vintage Book of Contemporary World Poetry Ed. by JD McClatchy

Each of these three books helps me to jumpstart my imagination in different ways, to think about the world in ways I could not have imagined without their help. They challenge me both as a writer and as a thinking human being. When we want to work out our biceps, we go to the gym and do some curls, but when I want to work out my imagination and intellect, I re-read these three books. I think I keep returning to them mostly because I don’t have them completely figured out. As a writer, I’m looking for authors that can give me new and unimagined possibilities in my art, new ways to move forward, and that’s what I find again and again in these three books.

A-town for life!