Heather Lang Cassera holds a Master of Fine Arts in Poetry with a Certificate in Literary Translation. In 2017 she was named Las Vegas’ Best Local Writer or Poet by the readers of KNPR’s Desert Companion. Her poems have been published by or are forthcoming with The Normal School, North American Review, Pleiades, South Dakota Review, and other literary journals and have been on exhibit in the Nevada Humanities Program Gallery. Heather curated Legs of Tumbleweeds, Wings of Lace, an anthology of literature by Nevada women, funded by the Nevada Arts Council and National Endowment for the Arts. She serves as World Literature Editor and book reviewer for The Literary Review, Faculty Advisor for 300 Days of Sun, and Co-Publisher for Tolsun Books. At Nevada State College, Heather teaches Composition, Creative Writing, World Literature, and more. www.heatherlang.cassera.net

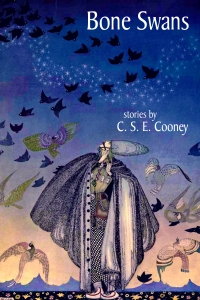

Heather Lang Cassera’s I was the girl with the moon-shaped face captures with near perfection something I have personally experienced, and I suspect, something a great many others have experienced as well: the upheaval a kid feels when their family as they know it is ending. It’s groundlessness but not floating. Peripheral, but awake.

She shows us the strangeness of change with the child’s inability to perceive the strangeness, ever shifting focus onto simple objects, and showing shades of what a kid’s imagination might have made them into. Even the softest of verbs here pierce, and the picture of the family is dismantled and carried by the speaker in pieces to adulthood.

As stark as a desert and yet rich with lattice and sprinklers, spilled milk, and steering wheels, I was the girl with the moon-shaped face is simply stunning. I have known Heather Lang Cassera for many years, and she has yet to disappoint me, in person or in prose. Let her chapbook stand as

Risa Pappas: There are themes as through lines in this chapbook, such as family, the peeling away of innocence that comes with growing up, and the changing perceptions of

Heather Lang Cassera: Thank you so much, Risa, for the warm words and for chatting with me about I was the girl with the moon-shaped face. I did write to explore the images and places around us in an objective-correlative kind of way. Also, especially in the later stages of the revision process, I worked to capture the unraveling of a family, at least as they have previously known it.

Something potentially notable about the girl is that her life is affected by the loss of her sister who she has never met, and this loss shines a specific light on her relationship with her living brother. Regardless, I hope the emotional truths stand in the forefront, transcending some of the narrative details, allowing a variety of readers to access the poems. I suppose grief and siblinghood might be added to the list of themes.

RP: What was the process? Was this always going to be a chapbook, or did it become one? Did you choose from poems you’d written or did you create them with a specific outcome in mind?

HLC: One of our MFA mentors, H. L. Hix, taught me to try each poem several different ways—even if only to confirm the first way was the best way, although the first draft is rarely the best draft in my case. I believe in this process. It’s proven to be some of the most sound writing advice I’ve ever received.

As you know, I frequently work with other writers on their manuscripts—through my role with Tolsun Books and elsewhere—and I often find that a poet’s poems are more related to one another than the poet herself might first expect. Sometimes the connections are anchored in a place. Other times the adhesive might be a recurring theme. These are just some examples. However, these loose ties that our writerly heart-brains sometimes accidentally create aren’t always enough to make a manuscript something more than a number of poems bound together in paperback. Rather, the order of the poems is often important, and in this way, I tend to look to organize the pieces so that, together, they create a larger story arc.

Many of the poems in this chapbook have been revised countless times, and many even after their initial publication in literary journals. This was to curate them in a way that they spoke to one another, that they created an implied narrative, one that tells the story of a singular speaker. Most of these poems were not originally crafted with this chapbook in mind.

Rather, while revising, I “met” (in a fictional sense) the speaker, the girl with the moon-shaped face, whose father’s fingers and palms became feathers and wings and, also, blunt. I felt compelled to tell her story. And as I did, I realized that, although I didn’t know it at the time, several of the poems I had written over the past few years were in her voice.

Also, for example, when I re-approached my stacks of poems, the grieving mother in one poem, the one whose thoughts remained above the terracotta roof, italicized amongst the bone-white clouds, seemed quite clearly to be the counterpart to the father in another poem, the father I just mentioned.

Something else a number of poems shared was the refracting of emotions through everyday objects, as you have mentioned above. And this felt singular to me, like something that could be a unique quality, a peculiar and noteworthy characteristic, of a singular speaker.

I have always wanted to write an origin story, and the girl with the moon-shaped face offered me this opportunity. I ordered the poems that felt as though they might be in her voice in a largely chronological way. Many had to be revised to exist in the first, instead of

RP: What are your feelings on the chapbook as a form, and what was your experience like creating one?

To me, poetry is

largely about concision. Yes, it is also about structure and music, for

example, but part of what draws me so magnetically to a poem is the hard work

each and every word must do. In this way, the chapbook, due to its shorter

nature, feels like the ultimate medium for poetry. Not only does it showcase

compact pieces of literature, but it is—in and of itself—succinct.

Sometimes, especially when it comes to a poet’s first full-length collection,

it feels as if the book is a gathering of a writer’s best hits, if you will.

I’m clearly generalizing, and there’s nothing innately wrong with a big bundle

of awesomeness! However, it’s more often unclear to me how or why the poems in

a longer book have been bound together—what conversations they’re having with

one another, what messages they are sharing collaboratively—than the poems in a

chapbook.

Also, let’s be real. I can fit a chapbook in almost any purse, piece of luggage, cubby, etc. This is important—because poetry should be everywhere!

Chapbooks are my jam, and I believe that they often do not receive the attention they deserve. What makes more words better? This is a loose metaphor, but I don’t know many folks who believe a five-minute song is innately better than a two-minute song. One of my literary endeavors is reviewing books, and I often choose chapbooks in an attempt to make a statement about the validity of them. Certainly, we could go off on a tangent about the history of a chapbook and the publishing differences, but today, when many presses are printing stunning chapbooks that are equal in aesthetic quality, I’m not sure why a 78-page paperback should automatically be deemed a greater accomplishment than a 28-page paperback, for example—especially in contemporary poetry, which is no doubt compendious.

RP: You are often consumed with other people’s works, editing a book of Nevada women’s writing, editing students’ work as a professor, serving as World Literature editor for The Literary Review, and editing for Tolsun Books. First, how do you find time in the day to write your own pieces, and second, how do you find the mental space to work on your own work in your own voice about subjects distinctly important to you?

HLC: While I find true joy in literary citizenship, immersing myself in other writers’ poetry and stories makes my own writing better. It’s sort of like a more extreme version of the old adage writers must read. In editing manuscripts with Tolsun Books, for example, I analyze every aspect of the work, from big-picture items, such as the narrative arc, to diction revision recommendations—sometimes down to a single word choice! And there’s some distance when it comes to working with other folks’ writing. It can be hard to see the downfalls in our own work because we can be too close to it. However, I learn so much from working with other writers’ stories and poems, and when it comes to craft, I try to make conscious efforts to articulate those discoveries in part so that I might later apply them to my own poems and essays.

Also, I’m going to go ahead and admit something. Sometimes reading submissions for The Literary Review, for example, is a bit of a procrastination technique. Some people watch YouTube. Others clean their house. Sometimes I dive into Submittable to read submissions when maybe I should be spending a bit more time on my own writing.

RP: It’s perhaps an understatement to say, but many of us are feeling exhausted, angry, dejected, scared, and hurt by recent social, cultural, and political events. Have you found yourself affected? How do you cope with these and other stressors?

HLC: As I work to answer this, so many recent events run through my head. I live in Las Vegas, and the effects of the October 1st shooting have been heavy on my Southern Nevada community. I also work at a Hispanic Serving Institution and was teaching the night of the presidential election, and I still can’t quite articulate the events and mood of my classroom on that evening as the results unfolded—although it is important to note that I’m a white woman and do, or at least work to, recognize my privilege as such.

On that note, when I’m

feeling debilitating down, the best thing I can do for my own spirits is to

help others. It shifts my focus away from myself. Maybe this goes back to the

bit about literary citizenship. I absolutely do not mean to sound high and

mighty. I have flaws. Lots of them. Even what I’m saying right here and

now—that I often help others to improve my own mood—might be rooted, at least

in part, in some sort of selfishness.

However, hosting readers for other poets in my Vegas Valley, for example, is

one way I bring hope into my community and into my own days. Also, my two dogs,

Maggie and Roxie Li, are beacons of light. I adore them. Risa, you probably

knew that we couldn’t make it through an interview without me mentioning my

pups!

RP: What do you hope people take from I was the girl with the moon-shaped face?

HCL: Hmm. Well, I am interested in hearing what others are taking away from the chapbook. You know. There’s that whole thing about how once you put your writing out into the world, it isn’t really yours anymore. What you hoped to communicate falls away. How the reader interprets the writing is what matters.

However, I very much appreciate the opportunity to answer this question! My wish is that the readers might find comfort through companionship in the more elegiac moments and that they might find hope in the glimmers of light throughout the pages as well.

Risa Pappas is an award-winning filmmaker, published poet and freelance writer. She is also an editor at Tolsun Books. A professional rebel, Risa’s areas of focus are intersectional feminism, professional wrestling, and tea. She lives in Philadelphia with her cat and an alarming number of houseplants.