According to Hurwit’s features of the Archaic style, there are several common themes of this time period — “reliance on schemata,” “impulse for pattern,” “domination of surface and plane,” linearity, ornamentality, and “explicitness and impassivity.” While these are obviously traits that imply art in the sense of visual arts, there’s something to be said for how the traits of visual arts seep themselves into the nature of writing. Drawing was the first writing, anyway, so it makes sense that the two as sister mediums would communicate into each other. This shows the role that the power of imagination plays into humanity’s understanding of art, and how words and visual arts would be lost without each other. Much like how visual art of the Archaic period embodies the images of the Archaic style, so do the very literal and image-based works of Sappho, without ever actually drawing anything.

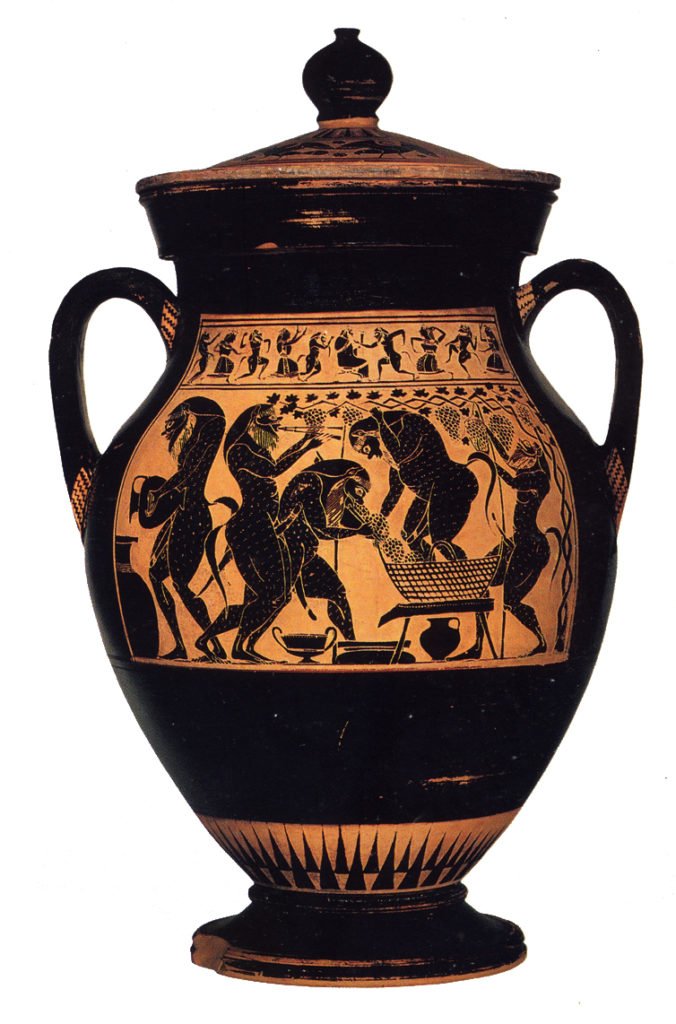

The Amphora by the Amasis Painter is a magnificent, detailed image. It’s a vase, featuring the image of five men and one woman. There is a geometric, linear crest at the top of the image, and below all the people can be seen gathered around a table with a basket on it. Inside the basket, there is one of the men standing up. Four of the men are naked, have tails, and abnormally large penises, which, judging by background knowledge, means that they are satyrs. One of the men is robed and has flowers in his hair. All the people are carrying vases and goblets, which would probably imply drinking. For this reason, the robed man is probably Dionysus, the wine god who is associated with satyrs. The woman appears to be scolding the men, and is fully clothed. One of the satyrs is right beside her, and she has her arm around him. She is possibly dating this satyr, or she is pulling him away.

Along with being beautiful, this image is also a fantastic example of the features of the Archaic style. The content has an obvious reliance on schemata — one would need to know the common themes of satyrs, Dionysus, and drinking in order to be able to put together that this was a scene of all of that put together. While men are already usually portrayed naked in ancient Greek artwork, there is something to be said for how the contrast between the satyr’s nudity and Dionysus’ clothing brings a statement about the difference in mortality between the men. The men are in the typical tan and black contrast of ancient Greek pottery, and the linear pattern at the top of the image is less rigid than the rest of the image. The people are in very linear, stiff positions, and so are the satyr penises. The image takes up the entire top front of the pot, and there is very little blank space in the image. None of the people are drinking, it is merely implied by symbols such as the goblets and vases. Since this is on a pot, this means that this piece is not just ornamental in an aesthetic way, but in a practical way, too. While it is a pretty design, it also tells a story about Greek mythology, which is important for a culture that was widely illiterate. While the image has symbols, it is mostly explicit and impassive — it’s clear who these people are, what they’re doing, and the men behave oblivious and uncaring to the woman scolding them (Biers, 184).

However, the Archaic style doesn’t just stop at images. The Greek poet Sappho also embodied these traits in many of her poetic fragments. “Now, today I shall / sing beautifully for / my friend’s pleasure” Sappho explicitly declares what she intends to do — she is a lyric poet who wants to share her work with the world. This also shows an impulse for pattern, because she very much keeps up a pattern of lyric poetry throughout her work. This is linear in the sense that it is literally just a sentence (Fragment 1) “As for him who finds / fault, may silliness / and sorrow take him!” This continues Sappho’s pattern of explicitness, and it also includes impassivity, because she’s saying that she doesn’t care about people who don’t like her work (Fragment 2).

“Only breath, words / which I command / are immortal” This continues Sappho’s explicitness and impassivity, while she writes yet again about her own voice in the world. She explicitly states what she can make last forever, while implying her own apathy over her lack of an ability to do the same for everything else. It is linear in the respect that it directly tells things in an order mimicking how these would fall in the passage of time — breath, then words, then immortality (Fragment 9).

“Girls ripe to marry / wove the flower – / heads into necklaces” This uses an impulse for pattern — the themes of flowers and marriage are in every line, making it a strong visual. The girls are “ripe” to “marry,” and “wove the flower – / heads into necklaces,” which was a popular wedding tradition in ancient Greece. This also means that this fragment shows a reliance to schemata, because the intended audience would’ve been ancient Greeks who would’ve already known about that.

However, as Sappho mentions in Fragment 9, she expects her words to last forever, which must inadvertently mean that A) she knows that details like this will become obscure to her newer audiences, B) she is confident that something like wedding flower crowns will be preserved as a tradition because of her poetry (which, it has), C) she knows that the context will make this poem still make sense in the present time, or, D) all of the previous choices are looking way too much into this because it also very easily could be something that she doesn’t put much thought into.

The flower necklaces are an obvious form of ornamentality — while she is very blatantly describing a wedding, she focuses on symbols of a wedding, such as girls and flower crowns (or, if you want to get really technical, girls making flower crowns), rather than the wedding itself. She creates linearity by first describing “girls,” then mentioning that they’re “ripe to marry,” and then implying the ceremony by describing them creating the flower necklaces. She uses explicitness by very clearly describing girls creating flower necklaces for a wedding, which is a very easy image to understand (Fragment 10).

“FIRST VOICE: Young Adonis is / dying! O Cytherea / What shall we do now? / SECOND VOICE: Batter your breasts / with your fists, girls — / tatter your dresses!” This uses a very heavy reliance on schemata — it requires that the audience knows who Adonis and Cytherea are. As was mentioned previously, in the analysis of Fragment 10, this is because the audience is ancient Greeks, and because Sappho believes that her writing is immortal (which it has (mostly) been so far), this also shows that Sappho believes that ancient Greek culture is immortal, too (which, one could also say, it mostly has been like that, too, so far). Adonis is the romantic partner of Aphrodite, and Cytherea is another name for her. This fragment shows linearity by telling a linear story, and ornamentality by focusing on symbols of heartbreak, such as Adonis and Aphrodite, instead of just heartbreak itself. One could fall into the trap of thinking that this means that this poetry is a metaphor for Sappho’s own heartbreak — but one could also argue that it isn’t. Because Sappho comes from a time where poetry is written in a very “literal” way, it’s unlikely that she’s writing about anything other than just the heartbreak of Aphrodite (Fragment 11).

“And they say about / Leda, that she / once found an egg / hidden under / wild hyacinths.” This also uses reliance on schemata, since it requires the audience to know that Leda was a princess of Sparta who Zeus seduced while taking the form of a swan. She laid an egg, which Helen and her twin brothers hatched from. However, some versions of the myth say that the goddess of vengeance, whose name is Nemesis, was the one who laid the egg, and that Leda simply happened to find it. With this knowledge, this makes it very linear, ornamental, explicit, and impassive. Sappho chooses yet again to write about the egg instead of Helen and her twin brothers, and writes bluntly about the more negative version of the myth. She states clearly and sequentially to create the image, and shows what she either believes of the myth in contrary to the other one, or just what she believes of the myth, not in contrary to another (Fragment 13).

“Ambrosia stood / already mixed / in the wine bowl / It was Hermes / who took up the / wine jug and poured / wine for the gods.” Sappho has kept a noticeable pattern for themes of nature and Hellenistic mythology. She uses ornamentality yet again, by focusing on symbols of the gods, such as ambrosia and wine, to tell stories about the gods themselves. Her linearity goes hand in hand with her explicitness, and sometimes also her impassivity. In this case, by writing about Hermes in this way, she tells about the work that Hermes has to do, and how as a messenger god, he often has to work similarly to a servant — even though he’s one of the most powerful gods in Hellenistic mythology (Fragment 14).

“On his way down / from heaven, he / wore a soldier’s / cloak dyed purple.” Explicit, yet (probably) still requires background knowledge. Who is this soldier, anyway? It is common knowledge that purple has historically meant royalty, because that was once a very expensive dye to make. This might be talking about a god (Fragment 15).

“Hesperus, you herd / homeward whatever / Dawn’s light dispersed / You herd sheep — herd / goats — herd children / home to their mothers.” This uses reliance on schemata — one would need to know who “Hesperus” is, and presents in a linear way that communicates animals and children being guided home by the evening star, which is Hesperus. It’s easy to fall into the trap of thinking that Sappho’s work is all deeply complicated metaphors, which would be understandable if she happened to be a modern-day poet, but she’s not. Sappho lived in a time when poetry was much more direct, since ancient Greeks in her time were mostly illiterate and poetry was recited instead of written. Sappho was also a songwriter anyway, giving her a very similar role to lyric poets such as Homer. Therefore, as explicit and impassive as this can be, Sappho was literally just writing about the evening star, and the vulnerable young who are following it home.

However, while this might not have the same meaning as how a modern poet would write this, there’s still beauty to the images that Sappho’s poetry creates — she is merely embracing the beauty of the evening star guiding children and young animals home. Poets like Sappho show that an image doesn’t need to be a metaphor to be beautiful, because there is already so much beauty in the world of nature, and gods, which is an important reminder to a modern society where poetry is (usually) expected to be chock-full of metaphors. Sappho isn’t constantly talking about herself; she’s just writing about the beauty of her own surroundings (Fragment 16).

“I have a small / daughter called / Cleis, who is / like a golden flower / I wouldn’t / take all Croesus’ / kingdom with love / thrown in, for her.” Linear, explicit, and impassive — like all of her other work, this is straightforward, and when she talks about herself, she just says it instead of using metaphors like how a modern poet would. One could argue that she did use a simile, BUT, that’s not the same thing as a metaphor. This poem shows impassivity in the sense that she “wouldn’t / take all Croesus’ / kingdom with love / thrown in, for her,” which shows a very different side to impassivity than what most people usually think of. Rather than writing about impassivity in a negative context, Sappho writes about impassivity in a positive context — that she loves her daughter so much that she doesn’t care about anything else that could possibly be offered to her. This yet again shows the beauty of Sappho’s very literal, non-metaphorical writing — because she isn’t focusing on metaphors, she instead takes the nature of literal writing and shows how she can twist it unexpectedly.

Provided, again, this is because she comes from a time where poets were expected to be literal and weren’t usually metaphorical, but it still goes to show that Sappho manages to use this to contrast in a time where literal poetry was the norm, and now contrasts even more in a time where metaphorical poetry is the norm. This poem uses linearity in the sense that it implies a possible future trade offer. It also uses reliance on schemata because it expects the audience to know who Croesus is. He was so rich that he was widely known as a symbol of high wealth, and, of course, he was the king of Lydia. This means that Sappho is saying that she wouldn’t trade the greatest of riches for her daughter who she loves so much. A simple comparison, yes, but, again, that’s the beauty of Sappho’s poetry — she makes the extraordinary out of the ordinary. She shows that the simplest things still have value to them. She shows ornamentality by using symbols such as “a golden flower” and the riches of Croesus’ kingdom of Lydia to “symbolize” her points, even though she is, again, not using metaphors.

Sappho’s pattern of focusing on objects shows just one of the many ways that one can create visuals and personification while still being perfectly literal. Sappho’s fine craft at literal poetry shows that she can dominate surface and plane, because she is using every last square inch she can of what it means to write visual non-metaphorical poetry about her own surroundings (Fragment 17). Words and visual art are an intertwined medium — and the beauty of that is that this is communicated through both mediums quite well in the Archaic period of ancient Greece. While Sappho’s poetry fragments and the Amasis Painter’s Amphora hold their differences between mediums, the two still hold a theme of telling blatant, meaningful stories out of the context known by ancient Greeks, which is illustrated quite well using the methods of the Archaic period.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Biers, William R. The Archeology of Greece. Cornell University Press, 1996, pp 184.

Sappho, and Mary Barnard. Sappho: a New Translation. University of California Press, 2019.

Mercury-Marvin Sunderland (he/him) is a transgender autistic gay man from Seattle with Borderline Personality Disorder. He currently attends the Evergreen State College and works for Headline Poetry & Press. He’s been published by University of Amsterdam’s Writer’s Block, UC Riverside’s Santa Ana River Review, UC Santa Barbara’s Spectrum, and The New School’s The Inquisitive Eater. His lifelong dream is to become the most banned author in human history. He’s @Romangodmercury on Instagram, Facebook, and Twitter.