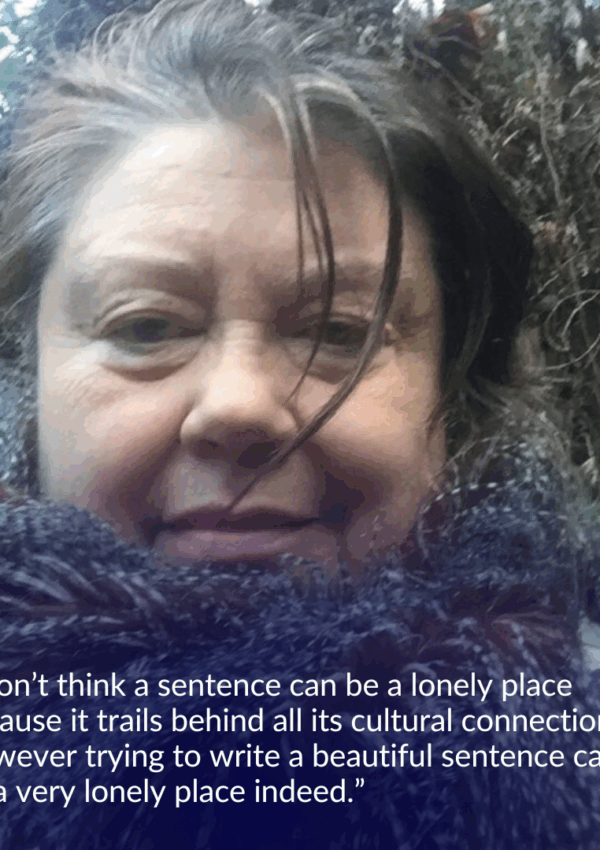

Emily Hoover is the author of the novella in stories, Snitch (Wordrunner eChapbooks, 2021), and the poetry chapbook, My Mother as a Serrano Pepper (Zeitgeist Press, 2023). Her poetry, fiction, and reviews have been published by Sundress Publications, Rinky Dink Press, Maudlin House, The Citron Review, Cleaver Magazine, Necessary Fiction, Ploughshares blog, The Rupture, and others. Her creative works have been nominated for the Pushcart Prize, Best of the ‘Net Anthology, Best Small Fictions Anthology, and Best Microfiction Anthology. She lives in Las Vegas and serves as a Lecturer of English at Nevada State University and a Priority Editor at Flash Fiction Magazine. Find her on Instagram and Twitter as @em1lywho.

Heather Lang-Cassera: Thank you, Emily, for chatting with me about My Mother as a Serrano Pepper, forthcoming with Zeitgeist Press on November 1st of this year. Your chapbook holds some of the most palpable and resonant elegiac poems I’ve encountered in years. Thank you for sharing this complex, and incredibly important, poetry collection with the world.

When reading My Mother as a Serrano Pepper, something I notice immediately is your masterful use of enjambment. I think of a few lines from “Schizoaffective Disorder”:

Now: your voice, wrapped

in mania,

when plants arrive on Mother’s

Day. You won’t open

the box—

The break after “wrapped” highlights this word and seamlessly merges the physical gift with the emotions of the poem, making even more tangible the speaker’s experience. Similarly, by breaking after “You won’t open,” we have the literal information, “You won’t open / the box,” but also the connotation of the disconnect, a closing off, that we might experience between family members and especially amid mental illness.

Emily, for our readers, I’ll mention that we work together as educators teaching Creative Writing and more at Nevada State University. I think about the ways in which we discuss elements of poetic craft with our students. Might you be willing to talk a bit about how you approach line breaks in the context of your work?

Emily Hoover: Thanks for this wonderful question, Heather. All of the micropoems in the chapbook came from one larger prose poem, originally. Rather than keeping the prose poem that contained all these vignettes, I decided to tighten them and split them up into several micopoems. As I primarily write flash fiction, I felt called to distill these moments into tight vignettes and spread them out in the collection. This choice allowed me to amplify the fragmentation and powerlessness the speaker is experiencing as she navigates her mother’s worsening illness.

Regarding enjambment: when I began lineating the poem—moving away from the lengthy, boxy prose poem shape and isolating the vignettes into several micros—I knew I wanted to break my lines on verbs in order to keep the poem(s) moving quickly. Pacing, tension, and urgency are always thoughts in my mind, whether I’m writing poetry or fiction.

“Wrapped” was a choice on which I meditated for a while because it’s an active verb, but the enjambment also conceals the phrase, “wrapped in mania,” which makes the image more surprising when it is encountered. When we think of being wrapped in something, there’s often a connotation of being held or supported by a good force, but “in mania,” on the next line, complicates that. It defamiliarizes the verb “wrapped,” which is more in line with the speaker’s mother’s situation.

I feel similarly with “open.” The first part of the sentence, “You won’t open,” confronts the whitespace on the page and, as a result, adds another layer of meaning. Instead of just communicating that the speaker’s mother won’t open the gift box, the divided line is also saying that the speaker’s mom is afraid—she can’t open or surrender or trust.

I like how weighted these lines you mentioned are, and enjambment is one way I like to add weight to poems that are already heavy in theme.

HLC: I admire the ways in which you consider form and other poetic elements in light of the gravity of a poem’s content. Emily, you mentioned that you primarily write flash fiction. Might you talk a bit more about how your experience with that genre affects your poetry? Perhaps similarly, did any element of narrative play a role in the ordering of the poems within your chapbook?

I appreciate the cohesion of My Mother as a Serrano Pepper. I tend to prefer collections in which the pieces fit together in a clear way; otherwise, I might prefer broadsides, postcards, or some other unbound form of publication. The time that I spend with your collection as a whole allows me to experience each poem more fully.

EH: Writing flash fiction has definitely made me a better poet! I’m also grateful for my time as a journalist in high school, college, and grad school. Flash fiction and journalism taught me how to be urgent without being simple and how to harness tension with as few words as possible.

I used to think I wasn’t a poet because I’ve spent my life spellbound by narrative (as a consumer of fiction, nonfiction, and film). I love the combination of voice, tension, and events, and that’s probably why my earliest publications were conventional short fictions between 3,000-5,000 words.

However, poetry has taught me that some things in life don’t make sense as stories—or perhaps as conventional stories with cohesive narratives. I started writing this book in early 2019 when my mother was institutionalized for the first time, and it felt like nothing made sense. I couldn’t write or share this event as a story, so poetry was something I tried. I was able to concentrate on the emotional truth and imagery of the situation while foregoing characterization and avoiding tragic events.

At least, that’s what I thought. Now, when I look at the book, I see two stories. It’s a story about me (my speaker—who’s a version of me) and a story of my mother’s complex traumas. She’s the focus for several poems, but when I started putting the poems together into this chap, I realized the story is me learning to accept myself despite the dysfunction of my childhood. So, I’m the narrator, the one who’s witnessing, until the last few poems, which force me into action. This poetry isn’t separate from the storytelling elements I’ve learned and teach my students; it just goes after these elements in different ways, ways that are more image-heavy, sonic, and fragmented (regarding plot) than my earlier fictions.

I’ve leaned into flash and micro fiction while writing and revising this book, and I’ve found many similarities: poetry and flash/micro fiction encourage the writer to balance concrete and abstract language but also lean into ambiguity. I like looking for that balance in my work. Also, flash distills the storytelling elements until they are barely recognizable: just yearning, urgency, and tension. I like to think my book has distilled my life into those elements, too.

HLC: I absolutely witness the ways in which your expertise in storytelling has led to the intentional topography of the chapbook. Thank you, Emily, for sharing your path and your process.

You mentioned that your poetry approaches storytelling in, in part, a sonic way. Might you talk a bit about that aspect of your work? I’m curious: is sound important to your poetry from the first draft, or is it something you infuse as you revise? Similarly, are there certain poems you tend to read to audiences because of their attention to sound, or are those decisions made mostly according to other factors?

EH: Unless I am working in a form that requires that I pay special attention to sound—as you know, the chap has a sonnet and two pantoums—I don’t write with sound in mind until I am revising. Sometimes, when I’m working on a line, I’ll notice some assonance or alliteration. Generally, I don’t see those patterns until I read the lines aloud. I read my work aloud a lot, almost obsessively, when I’m drafting and revising. So oftentimes, sonic elements—especially internal rhyme, usually slant rhyme—happen later. I might change verbs to add some echoes or even break lines to conceal repetition or rhyme. Just like with my fiction, I practice the COAP method: cut, order, add, polish. Sound is usually something I think about intensely after I’ve moved through the cutting stage.

When I’m choosing works to read publicly, I do think about sound. I often read “Risperidone” aloud because it has no punctuation. The disorganized thinking and language associated with schizophrenia are less confusing when read aloud rhythmically, I think. Also, that poem has a refrain, so it’s one I read a lot. I like to read my sonnet “Pain Constellation” aloud, too, because I disrupt the rhyme scheme with enjambment and slant rhyming, so that’s fun to share with a crowd.

HLC: I love that! Emily, I am very eager to hold a print copy of My Mother as a Serrano Pepper in my hands—and to hear you read from this deeply resonant chapbook! Thank you so much for taking the time away from your teaching and writing to chat with me and for sharing these poems with the world.

About the Interviewer:

Heather Lang-Cassera is a full-time lecturer with Nevada State University, a Tolsun Books publisher, and a 300 Days of Sun Faculty Advisor. She was a 2022 Nevada Arts Council Literary Arts Fellow and the 2019-2021 Clark County, Nevada Poet Laureate. She is the author of Gathering Broken Light (Unsolicited Press, 2021), which was written with the support of a Nevada Arts Council grant and won the NYC Big Book Award in Poetry, Social/Political. Her next collection of poems, a book of ecopoems with the working title of Firefall, has been acquired by Unsolicited Press for publication in 2025