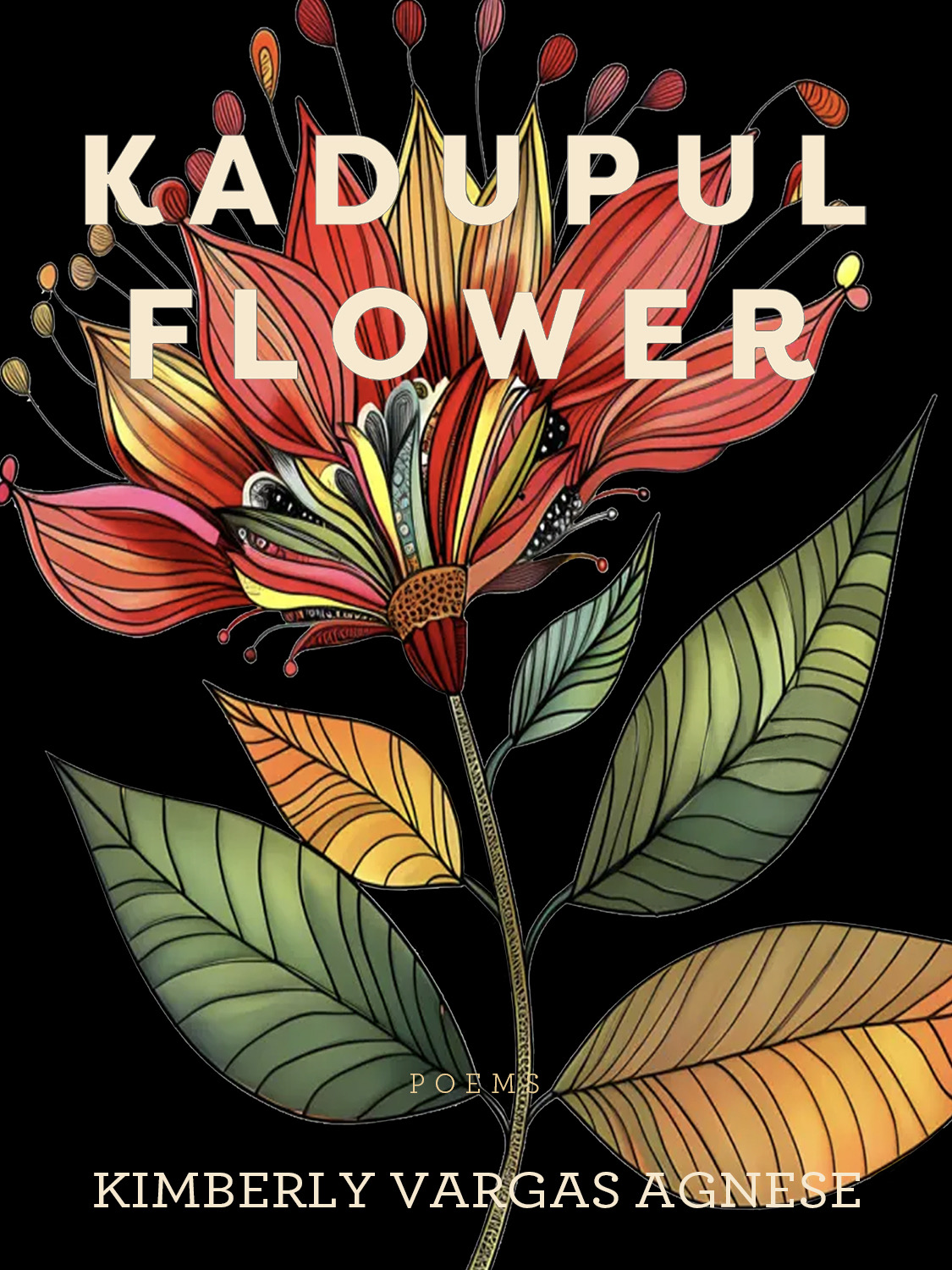

Kadupul Flower by poet Kimberly Vargas Agnese will be released in October 2025, published by Green Writers Press. Agnese is an accomplished Chicana poet whose work has been featured in publications such as Anacua Literary Arts Journal, The Seventh Wave, Awakened Voices, Rappahannock Review, and The Clay Jar Review. For over 30 years, she has resided in Fresno, California, where she continuously writes and is an active member of her community. She shares a home with her daughter. This collection of hers has finally come to fruition after seven years of writing, revising, editing, and connecting with others.

This full-length collection is Agnese’s debut poetry book, expressing integral themes displayed throughout her life and her perception of the natural world. Dissecting her life as a Chicana writer, devoted Christian, educator, environmentalist, and mother, and as a human being, Agnese embraces the beauty and acknowledges the unjust parts of living in Fresno, California. Written in seventy-four pages, the collection contains thirty-one poems that express cultural heritage, familial connection, geographic and migrant exploitation, and the capitalization of land and natural resources. Many of her poems address the emergent signals of late-stage capitalism, the lack of humanity towards those affected by economic inequality, ecological justice, and generational aspiration. By doing this, Agnese intersectionally speaks to environmental, social, and racial issues that pollute the quality of living in America.

“These blue seas and sobbing coasts,

green webbed stems and voles

meadow crusts and pocketless sunflowers

bending towards the orb

are a kind of gold that wilts when cut.

– Kimberly Vargas Agnese, “Our Inheritance”

Angelina Hund: Like many agricultural hot spots, the stock produced in Fresno, California, profits large companies, leaving workers and locals with a deficient food supply at unaffordable prices. How has living in Fresno as a mother and educator shaped your perspective on food systems and inequality? What motivates you to address this issue—is it rage, ambition, or a desire to shed light on underrepresented voices and suppressed stories?

Kimberly Vargas Agnese: I was made here. In my young adult years, I was raising four children. I remember praying about how the twelve dollars I had for the week would feed the six of us. Lentils, rice, and an onion can go a long way. Later, as a single mother, I also remember the kindness of strangers who, watching my face turn red at the checkout line, offered to buy the rotisserie chicken in my cart. I hadn’t realized it couldn’t go on the food stamps card. This type of thing happened more than once: People seeing me, not my poverty.

As an educator, I remember the kindness of the lunch ladies. The students knew that they could visit the cafeteria at any time if they hadn’t had enough to eat at home or had not eaten at all. There is a way among us of sharing and caring… for those of us who know.

My motivation is a sense of calling: a frustration at how a nation that calls itself Christian doesn’t seem to have eyes to see or ears to hear or a value system that cares about the value of the vulnerable communities among us. Communities made vulnerable not by our own doing, but because of the present system. Being labeled as “lesser,” and thus being exploited.

There is the exploitation of life-givers, of those who pick the food we eat, of women, of the land, of the poor—whom I have often found to be the most generous among us. This shows me that something is amiss in our value systems. When we attempt to weigh one another on the scale of capitalism, we are the ones who come up lacking. We are exchanging individual contributions for dollar signs.

I was called to teach: not to mold children into a very narrow idea of how they will benefit a capitalistic society, but to empower them to believe in who they, and their peers, were created to be. I have taught beautiful daydreamers, budding poets, passionate leaders, and brilliant young people who were told that something was wrong with them.

AH: Politics are personal, and poetry is very personal. Your book addresses economic and social issues such as pollution, environmental abuse, and class inequality and highlights the migrant experience, among countless other things. What is your goal in spotlighting these issues? What do you hope readers will learn while reading Kadupul Flower?

KVA: I want to do my part to bring awareness, to impart heart, which might motivate the reader to bring their best. To not forget the great among us who society considers less.

AH: Your poems discuss homelessness in such a headfirst manner, which is necessary. Often, people tiptoe around the subject, even though we all know it is a pressing issue. How we view, treat, and understand homelessness is reflective of society’s priorities and values. Why is it so important to you to address misconceptions and biases about the homeless population?

KVA: The poems about those without homes are closest to my heart. I’ve worked at a rescue mission and served as a youth pastor to this population. Having given and received so much from them, the misconceptions about these people drive me a little crazy. These neighbors have been my friends. Some within this demographic are my heroes, whose strength of character and sense of community is not often found elsewhere. I remember Lisa, who offered me and my daughter all the coins she had collected that day so that we could “get something for our Thanksgiving.”

Somebody needs to explain to me how these people, who are judged for having so little, are willing to give so much of what they have…when those who have so much refuse to. And how that makes them “less.” Surely the great walk among us unseen.

AH: As we breach farther into late-stage capitalism, we often see food and fresh produce that are inaccessible and overpriced. It has become a luxury that often leads poor families to make sacrifices for nutrition. Either you can buy fresh produce or buy something that will last the week. Your poem “Kadupul Flower,” which shares a title with the book, highlights this. Why did you decide on this to be the title of your poetry book?

KVA: For many, many years, my being on food stamps and living beneath the poverty line has indeed evoked much prayer about what to buy or fix and what not to. Although we are now in the lower middle-class income bracket, we are still recovering from years of living like this. Presently, there’s a huge hole in our roof. Our bathtub is rusted out, and the washing machine is broken. But we eat well, live in a beautiful young food forest that is home to many creatures, enjoy each other’s company immensely, and laugh a lot. We’re blessed.

That said, the trajectory of the poem “Kadupul Flower” is about commercialization as a whole—the all-too prevalent bent that money is indicative of value. It is also about the strength and dignity of those who are not considered to be “worth” much. It is the strength and dignity in this poem that Stephanie (who picked the title) thought encompassed the collection.

AH: As a poet who has had their writings published in several works, including Anacua Literary Arts Journal, The Seventh Wave, and The Clay Jar Review, how does it feel to have your debut poetry book published? Can you speak on the process and how it is different from being featured in collaborative magazines and other publications?

KVA: Stephanie has always believed in me as an artist, even when I didn’t believe in myself. When she was young, she found a picture I had painted and thrown away, pulled it out of the garbage, and taped it up in her room. When she came home from college, she said, “Mom, I think I can get your poems published.” After they made appearances in lit journals, she wanted to enter me in contests. She was the one who compiled the collection which was named a finalist in the Andres Montoya Poetry Prize contest from Notre Dame. After this, Stephanie wanted my work to be published in a book—not an online book, but a real hold-in-your-hand traditionally published book.

As a mother, I’m delighted to see all this happen. On a personal note, getting published at this level is an affirmation that I am called to write—that all my suffering, all my neurodivergent oddities, make sense for my purpose here on earth.

AH: How does working with Green Writers Press align with the social and environmental implications of your writing?

KVA: It was hot the day Stephanie and I sat melting in our front room, as she perused Submittable. Upon seeing Green Writers Press, she said, “This looks like a good fit for your poetry, Mom.” And I agreed. We have found very few presses that care about both the environment and the marginalized. I am thankful for the opportunity Green Writers Press is affording me to speak.

AH: What was the process of constructing this collection of poems? Have you been writing these for years, piecing them together for this project?

KVA: For about seven years, this collection has been in the works. The emphasis of the earliest poems was to advocate for those without homes, based on a sense of call to bring awareness. About five years ago, during prayer, Stephanie and I were called to rewild our suburban yard to provide a home for local creatures in need. I was shown that if we offered hospitality to these creatures, the Creator would send them here. After asking Stephanie if she was on board, she gave me an emphatic “Yes!” As a descendant of several indigenous tribes, I think that my temperament has always inclined towards this.

AH: After looking into you, I discovered you’re an educator for those who have complex needs, you’ve served as a youth pastor, and you are a literary coach. How has working with youth in your area influenced your craft/art?

KVA: Much of the child’s voice employed in my poems is a song in my head. It is the chorus of the children and youth I have had the great privilege of mentoring in and out of the classroom, the voice of my children, and of myself, singing together.

AH: Throughout the book, there are references to religion, prayer, and spirituality and mentions of the Bible. Can you speak on the importance of religion in your writing and how that is expressive of your identity? Is there a familial connection to spirituality? Is it meditative or reflective to incorporate this?

KVA: I identify first as a Christian and then as a native to this continent. I believe that I am called by the Creator to live and write as caring for the earth, per Scripture’s instructions. Throughout the Bible, I see the call to stewardship, the Creator’s care of the animals in the flood, and the mandate to care for the widow, the orphan, and the oppressed. Likewise, I am called to care for the most vulnerable, to value the earth and community like my ancestors, and to fellowship with the Creator and do His will.

Poetry is not my Christ. Christ is my poetry. Many of my poems come in prayer or dreams.

AH: Throughout the book, birds are often used to symbolize things in your writing. What is your connection to birds or wildlife in general?

KVA: I love birds. They utterly fascinate me. I feel at home when they are around. We have many who visit and live in our food forest: sparrows, doves, scrub jays, hummingbirds, flycatchers, and so on. In poetry, they represent many things to me: freedom, innocence, nature, hope, and community, among a few. They are our neighbors, and it just makes so much sense to include them.

AH: You often discuss raising the next generation in a world that values profit over land and natural resources. How does being a mother shape your perspective on these issues and influence the way you approach writing about them? And Stephanie, how does it influence you being “that” generation that is supposed to implement that change?

KVA: To me, responding to the call of environmental-advocacy writing is one in which I hope to bring awareness, not only for the sake of the earth we were made to care for, but also for the sake of the children dying from environmental oppression. Standing at the intersection of Christianity and environmental advocacy, I have learned that often, these two groups are seen as juxtaposed to each other, which brings division and a weakened effort for how we are all called to care for the earth. Many conservatively-churched people see environmentalists and caring for the environment as not important, not spiritual. But if the very first thing the Creator told us to do was to care for the earth, then it is one of the most spiritual things we can do.

Conversely, many environmentalists I have encountered have linked Jesus to the idea of environmental exploitation and colonization. However, greed, arrogance, and colonization are the destructive agents here. Not Jesus, who said that loving money was the root of all kinds of evil. That said, as a mother, I believe we all need to think deeper, go beyond these kinds of identity politics, and work towards a more thoughtful future. I would like that for my children.

Stephanie Agnes-Crockett: My participation in the environmental movement was born out of having this incredible opportunity to live with my mom and to be under her mentorship. My environmental feelings are very much shaped and influenced by my mom’s wisdom in accordance with our shared Christian faith.

While learning to pray, Anne Shirley of Green Gables fame describes the worshipful posture that nature evokes: “If I really wanted to pray,” she says, “ I’ll tell you what I’d do. I’d go out into a great big field all alone or in the deep, deep woods and I’d look up into the sky—up—up—up—into that lovely blue sky that looks as if there was no end to its blueness. And then I’d just feel a prayer.” This is a quote that resonates with me, as some of my closest encounters with Jesus have happened outdoors.

Since my mom shared about the calling several years back, I’ve been very moved by what the Lord has urged us to do in terms of rewilding. It has been an honor to cultivate the land alongside my mom: developing habitats and corridors for the wildlife, who have indeed taken up residence in our small, but ecologically diverse, landscape. Like many autistic people, I am drawn to animals. As such, I am delighted to “get to know” the creatures and insects around us: from the scrub jays who appear in front of the windows to demand peanuts, to the thirsty bees I rescue from drowning.

On the editorial side, it is a huge honor to contribute to my mom’s work as a poet. I am so grateful to support my mom in her calling, as she presents beautiful, anointed messages that reflect the heart of our Heavenly Father. It is incredible to be her daughter and to work with her in promoting these important themes.

Kimberly Vargas Agnese is an environmentalist Chicana poet who resides in California’s Central Valley. Her poems have been featured in numerous literary magazines across the United States, including Anacua Literary Arts Journal, The Seventh Wave, Rappahannock Review, and Awakened Voices, among others. Kimberly’s full-length collection, “Red String on a Saguaro Cactus,” was named a finalist for the 2022 Andrés Montoya Poetry Prize, awarded biannually by the Institute for Latino Studies at the University of Notre Dame.

Stephanie Agnes-Crockett is an educator, activist, book reviewer, and writer who is also working in the realm of publishing. Her writing has appeared in Brio Magazine, More to Life, and Purpose Magazine, among others. She holds her BA in Creative Writing from Biola University and received her MLIS from San Jose State University.

About the Interviewer:

Angelina Hund is a student from Bennington College and an editorial intern at Green Writers Press. Her focus on journalism, literature, and visual arts inspires her to explore cultural topics and issues affecting women, the LGBTQ community, and the neurodivergent community in her writing. Her work has been published in several regional newspapers, blogs, and magazines.

This is a very thoughtful interview of Kimberly. I applaud her for speaking her truth without hesitations at all.

Thank you Kimberly for your commitment to causes that hold dearly in your heart. 🫶

What a beautiful testimony to an incredible writer and author.

So fascinating. I am very very stoked to read this book, ladies! Will be ordering as soon as I can 🙃

This brought a tear to my eye: Somebody needs to explain to me how these people, who are judged for having so little, are willing to give so much of what they have…when those who have so much refuse to. And how that makes them “less.” Surely the great walk among us unseen.

Also, I loved: “Christ is my poetry.’” Wow. I love that deeply.

Thank you very much for this very thoughtful, thought-provoking, grounded and lush review, ladies! I enjoyed it very much 😊